Women & Veins: Why Gender is a Risk Factor for Venous Disease

Only women get varicose veins: true or false?

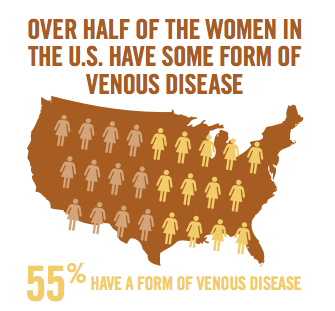

Although it is a common misconception that only women experience troublesome veins, the fact is, in the U.S. one in three people— including men— has some form of venous disease. That breaks down to 55% of women and 40 to 45% of men; of these, 20 to 25% of women and 10 to 15% of men will have visible varicose veins. Still, gender does make a difference.

Venous disease is defined as the impairment of blood flow back towards the heart. This occurs when healthy vein valves become damaged and the backward flow of blood "pools" in the legs or feet. Symptoms may present as discomfort, fatigue, or heaviness in the leg, causing varicose veins and other skin changes. Over time, the increased pressure can cause additional valves to fail. If left untreated, it can lead to extreme leg pain, swelling, ulcers, and other health problems.

Risk factors for developing venous disease, regardless of gender, include family history, older age and inactivity. Another significant risk factor— fluctuations in hormones— is related to gender.

According to Dr. Suzanne Jones, a board certified phlebologist and founder of Michigan Vein Care Specialists in Ann Arbor, a woman has three potential "high risk" times in her life that men do not. Significant hormonal fluctuations typically happen during menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause.

"At these times, hormone surges are very common for women," said Dr. Jones. "Progesterone can act as a vasodilator and cause the veins to stretch, sometimes enough for the valves to tear and subsequently fail."

Women who have venous insufficiency will often notice that their symptoms worsen during menstruation, for example.

What to expect

About forty percent of pregnant women are likely to develop varicose veins. During pregnancy, a combination of hormonal changes— specifically, greater amounts of estrogen and progesterone— and increased pressure on the abdomen can cause varicose veins to manifest. Interestingly, the most damage seems to happen in the first trimester, so those with known risk factors for venous disease should be instructed to wear graduated compression stockings throughout the first three months of pregnancy and possibly longer.

The volume of blood in a healthy woman increases by about 50% more than before the pregnancy, with the largest increase in the second trimester. With more volume to move, all of the blood vessels are under increased stress and veins can become very swollen.

In the final trimester, the expanding uterus can put pressure on the inferior vena cava, and further restrict proper venous return to the heart.

Pregnancy is also a time when women are more prone to blood clots, so phlebitis (inflammation of the walls of a vein that can cause a clot to form) can also be a concern.

It is not considered safe to treat varicose veins with aggressive treatments during pregnancy, advised Dr. Jones, but wearing good compression stockings can prevent them from getting worse and can go a long way toward relieving the symptoms.

"During pregnancy, the two most important preventative things to consider are periodically elevating the legs and compression," she said.

After labor, most women who had significant venous disease during pregnancy notice a big improvement after the baby is born, but it doesn't always resolve completely. Dr. Jones suggested that if patients have symptoms that are persisting several months later, they should be evaluated and treated.

"If a patient was uncomfortable because of her veins during the first pregnancy, then she should seriously consider seeking treatment between pregnancies—the next one could be pretty miserable if veins go untreated."

According to Dr. Jones, patients can be safely treated for varicose veins 6-8 weeks after delivery. Hormonal levels are back to normal within that time (if the patient is not breastfeeding), and water retention and any clotting risks have usually returned to baseline.

Depending on the type of treatment, breastfeeding may be an issue for some patients. Treatments that require a local anesthetic, such as endovenous laser ablation (ELVA) or microphlebectomy, have been proven safe. Sclerotherapy is not recommended if the patient is breastfeeding, as certain medications used during this procedure have not been proven safe and may be excreted in breast milk. However, if the patient is willing to forgo breastfeeding for 24 hours, sclerotherapy is possible.

Some vein specialists may recommend that women seek treatment for problematic veins before their first pregnancy, especially if there is a strong family history of vein issues.

The effects of aging

Even after menopause when most hormone fluctuations have stopped, a woman's risk of venous disease continues to increase with age. As the body gets older, a decrease in the production of collagen causes the veins to become weaker and the valves more likely to fail, especially in the superficial veins. For this reason, there is a higher incidence of varicose veins in the elderly population.

Older women may think varicose veins, or even leg ulcers, are a normal part of aging, but what many don't realize is that they don't have to live with symptoms. Even those who experience an aching or heaviness in their legs can receive treatment and relief. Treating the symptoms also arrests the progression of the disease. Treating the aching legs of a 60-year-old patient will improve her quality of life, and may also prevent a leg ulcer.

Post-menopausal patients who are taking hormone supplements should be aware of the increased risk of blood clots, which can damage veins or worse.

Additionally, the incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is higher in older people because of the conditions described as Virchow's triad (endothelium damage, stasis, and hypercoaguability). DVT occurs when a blood clot forms in one of the large veins—usually one of the lower limbs, such as the thigh or calf—leading to either partially or completely blocked venous return.

Physicians should consider recommending that their senior patients visit a phlebologist for a superficial venous evaluation prior to elective surgeries, especially hip or knee replacement. This step will help the patient learn her risks and decrease the chances of getting DVT.

Being proactive

Spider veins and varicose veins are health issues, but due to misinformation or dated attitudes, many women do not treat them as such.

Dr. Jones believes that it's important for women to be aware of venous disease and its symptoms and, as with any illness, to know the family history. (Someone with first-degree family members with vein issues, for example, will find her risk is significantly increased.)

Primary care physicians can be a great help to their female patients by: 1) listening to their concerns about their legs and veins, and 2) being knowledgeable about measures to treat and prevent venous disease.

With the right information, women have the ability to reduce their risk of developing venous disease and/or decreasing its severity. Preventative measures include: elevating the affected leg above heart level, wearing graduated compression stockings, living an active lifestyle, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoiding tight-fitting clothing and high-heeled shoes.

"Treatment of venous disease has progressed drastically in the last several years," added Dr. Jones. "Countless women have watched their mothers' and grandmothers' legs become terribly painful and unsightly, but that doesn't have to be their destiny."

This article was featured in Vein Health News, a publication founded by Dr. Cindy Asbjornsen to educate medical professionals and patients about vein health.

Dr. Asbjornsen is the Editorial Director for Vein Health News, Maine's vein magazine for primary care physicians. Read the Latest Issue and Subscribe to Vein Health News.

![]() Do I have Venous Disease?

Do I have Venous Disease?

Millions of people across the United States experience its symptoms. Find out more by asking yourself these 12 questions.

Request an Appointment

Request an Appointment

Ready to take the next step towards understanding your vein health and the available treatment options? Click here to request an appointment.